Indonesia’s agricultural sector accounts for more than 14 percent of the country’s GDP,[1] and agricultural workers are disproportionately impoverished compared to the rest of the nation. Nearly 80 percent of adults working in agriculture live on less than $2.50/a day, compared with 57 percent of those working outside of agriculture. The divide is even greater when you look at those living in extreme poverty — 18 percent of the agricultural sector lives on less than $1.25 a day, versus 9 percent of individuals outside of agriculture.[2]

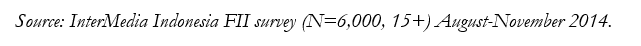

Women farmers face even greater barriers to breaking out of poverty than do male farmers or Indonesian adults outside of agriculture.[3] Women farmers score lower than all other adults on indicators of education, ability to generate savings that exceed debts, mobile phone access and bank account ownership. Yet, they maintain active financial lives, and are rooted in and important to the economy.

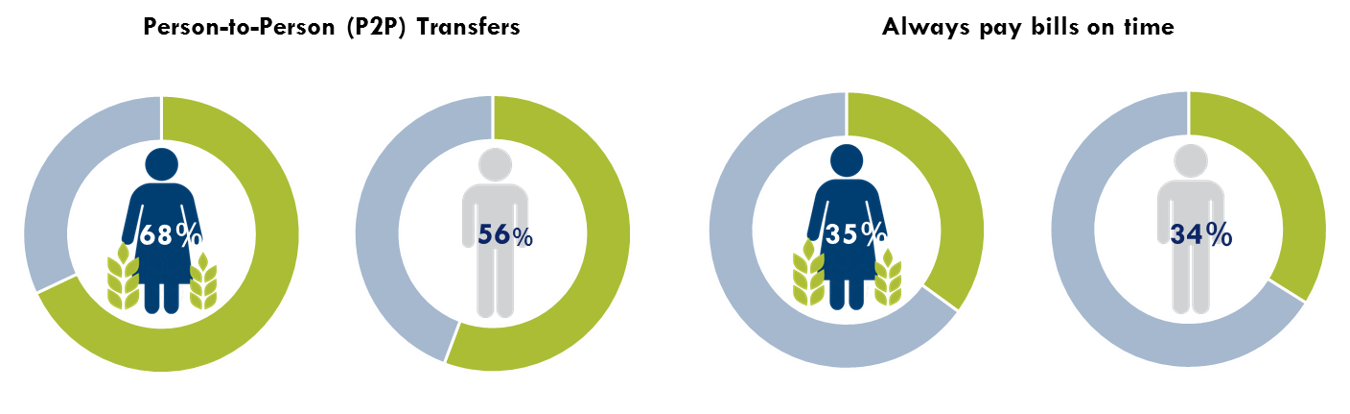

Our research also shows women farmers are as likely as other Indonesians to pay their bills on time and are much more likely to engage in person-to-person (P2P) transfers than all other adult Indonesians. Given their existing financial behaviors, women farmers would not only benefit from access to formal financial services, but they would likely prove to be a valuable customer base.

Without bank accounts, women farmers still engage in financial behaviors, but with increased risk.

The result of being financially excluded (without access to a formal bank or digital financial account) generally means conducting financial transactions in cash. This means having to physically deliver the cash, either in person or through an acquaintance, to pay for an item or make a transaction. Not only is carrying a large sum of cash a security issue, but the time and money required to engage in financial activities through cash takes away from the ability to be productive in other ways. As it is now, most of these women must spend the better part of a day and a portion of their incomes travelling and waiting in line to pay utility bills, or send money to friends and family.

Indonesia’s women farmers engage in financial activities that could be better facilitated through formal finance.

What keeps women in agriculture from opening bank accounts? Knowledge, cost and perceived value are the top barriers.

The role of mobile-based financial services

Helping women farmers overcome these barriers will be no small task for financial service providers. But, a concerted outreach effort by mobile-based financial services[4] (MFS) providers, implemented correctly, can address many of these barriers. In addition to simply offering financial services to women farmers, MFS agents, who work within their communities, are in a position to inform them of affordable financial products, and how these products facilitate their current financial behaviors. At the same time, they can walk them through the account registration process.

That mobile-based financial services could be a step towards bringing these women into the formal financial system is supported by early, positive news of ongoing, in-country pilots testing mobile-based financial services – such as the Mercy Corps Agri-Fin program. Once these pilot programs end, however, providers must continue to reach out to the consumer with information about available services and how to use them. In the past, Indonesian’s lack of awareness of available financial products has seemingly prevented greater uptake, an issue we looked at in our September 2014 blog: Is a Lack of Consumer Information Keeping Indonesians Financially Excluded?

Unbanked individuals and providers must join the push for increased financial inclusion.

Unbanked individuals and providers must join the push for increased financial inclusion.

The Indonesian government made a commitment to increase financial inclusion through the Maya Declaration, but without both unbanked individuals and financial service providers finding value in achieving greater inclusion, progress will be difficult. The question then is why should providers care and, perhaps most importantly, why should these women care?

Individuals

Financial inclusion can improve an individual’s financial security, and for these women farmers, it can also provide them with additional time to pursue meaningful activities. Rather than having to trust other individuals and informal services with their earnings – be it through arisans or money lenders– these women are able to keep their money safe in a formal government-regulated institution. This helps ensure their money is secure not only from fraud, but from theft and Mother Nature — all of which can easily cause losses when relying on informal institutions.

Inclusion in the formal financial system, and especially digital financial inclusion, can yield great substantial increases in free time that can be put towards acquiring new skills, working to increase crop yield, or other productivity-enhancing activities. Rather than losing many days a year to waiting in line and travelling to pay bills or send money to others, these women can conduct their financial activities in the blink of an eye and continue with income-generating work.

Providers

For financial service providers, financially excluded individuals are a lost source of revenue. In the short run, it is true that a bank may not see immediate returns on their investment in bringing in poor demographic groups such as women farmers. Long term, however, the added savings, ability to weather shocks, and the time savings they achieve by not using cash all add up to a greater opportunity to grow their incomes and savings, and put themselves in a much better position to utilize the financial products offered by providers.

Furthermore, actively engaging these groups reaps benefits for both providers and potential consumers. By reaching out to individuals rather than hoping they can find the time and money to travel to a brick-and-mortar facility, providers can educate consumers about how their products can help them manage their finances, while building brand loyalty. This investment in educating and equipping consumers with the tools they need to be good financial managers also will help decrease the likelihood of consumers defaulting on loans and create a sustainable source of revenue for the institutions.

What does the future hold?

If knowledge and perception barriers can be overcome, formal and digital financial services can enable Indonesia’s women farmers to better reach their potentials. With agriculture accounting for approximately one-seventh of Indonesia’s GDP[5] and employing nearly 40 percent of the population,[6] bringing digital formal financial services to key components of the value chain can provide a boost for the economy and serve as an important step to reducing poverty.

Sources

[1] World Bank Data 2013, accessed 4/29/2015

[2] FII Indonesia Survey (N=6,000, adults 15+, conducted August-November, 2014)

[3] This blog compares women farmers to other Indonesian adults (15+) as a whole. The author acknowledges that other subgroups in Indonesia may be equally or more marginalized than women farmers.

[4] Mobile money or mobile-based financial services products in Indonesia are both bank-led and MNO-led. MNOs are constrained by requiring a registered business entity to act as an agent.

[5] World Bank Data 2013, accessed 4/29/2015

[6] Grow Asia

More on Financial Inclusion Insights (FII) in Indonesia: